Writing for Beginners

In 2013, I had the honor of speaking at Build in Belfast. I want to thank Andy for inviting me and bringing us together.

Today, I want to talk about writing as a practice—as something beginners do—and how that relates to design.

Earlier this year, I got into this concept of the beginner’s mind. I realized that being a beginner is really fulfilling for me. All of the things I enjoy doing are things I just like practicing; it’s not about achieving a particular goal or trying to one-up myself.

When we’re beginners, we come to things playfully and curiously. We’re open to trying different approaches and making messes to figure things out. And I didn’t know it at the time, but beginner’s mind is a Buddhist concept. The Japanese word for it is shoshin. It refers to having an attitude of openness, eagerness, and a lack of preconceptions.

Suzuki Roshi talks about this extensively in his book, Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. He says:

“In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few… In the beginner’s mind there is no thought, ‘I have attained something.’ When we have no thought of achievement, no thought of self, we are true beginners. Then we can really learn something.”

When we’re writing and designing, it’s our job to be open to possibilities and explore them through our practice. If we approach our work with a beginner’s mind, we can peel away those layers of expertise and see things as they really are.

In Writing Down the Bones, Natalie Goldberg says:

“That beginner’s mind is what we must come back to every time we sit down and write. There is no security, no assurance that because we wrote something good two months ago, we will do it again. Actually, every time we begin, we wonder how we ever did it before. Each time is a new journey with no maps.”

We can have our templates. We can have our tricks and toolkits, but just because something worked in the past doesn’t mean it’ll work now. Those things don’t necessarily make it easier to start. We have to see each problem for what it is.

This is why I’ve started thinking of myself as a perpetual beginner. It gives me a license to ask questions and try new things, and it also takes the pressure off of knowing everything. I don’t need to be a perfectionist. I just need to stay attentive. That’s the most important thing I can do.

Perpetual beginner

To keep a beginner’s mind, I practice a lot of different things and think about how they relate to each other. Right now, I’m learning to be a(n):

- author

- business owner

- wife

- home cook

- surfer

- speaker

I hope you’ll be patient with me on that last one today. So let’s talk about writing as a practice, as way forward, as something beginners do.

The difficulty of words

Let me ask you a question. How many of you have tried to write about something that you love or know very well, but found it incredibly hard to write about?

I have this trouble all the time. It’s completely normal, even for someone who works with words every day.

This is from Toothpaste for Dinner by Drew Fairweather.

Words are how we relate to things. But even when we know what we want to talk about or know the subject very well, that doesn’t mean it’s easy to put into words. It can be really hard to get to the heart of something.

Myths

I think popular images of writers make this harder on us too. We come to the screen and the page with a lot of ideas and often put those before what we’re writing about.

Bullshit about writing

Here are a few of those myths. If you want to be a writer:

- You need to know what you mean to say.

- You need a plan, a thesis, or an outline.

- You shouldn’t wander or ramble. Keep things under control.

- You need to be tortured or completely addicted to something.

- You need inspiration or a muse. You need a thunderbolt and you need it now.

This is bullshit. I’ve been writing for years and I don’t believe a word of this. And I empathize with anyone who has ever struggled with any of this. It is completely normal to struggle with these feelings, but this is total bullshit.

To not knowing

We talk about writing as if it comes from a place of knowing, a place of understanding. We leave out the messy parts. We wait for inspiration or an epiphany. But I would propose that writing comes from a place of not knowing — a place of exploration, seeking clarity, and wanting to communicate. A place for beginners.

So what if, instead of thinking about writing as a way to transfer knowledge from one brain to the next, we thought about it as a way to build understanding? First, in ourselves, in our minds, through the process:

- thinking

- noticing

- asking questions

- jotting down ideas

- massaging what we’re trying to say

- taking in feedback

- working through drafts

Then, once we have something to show to a broader audience, writing becomes a way to build understanding with readers, and if that’s an internal audience, with clients or coworkers.

Words help us understand the world and express ourselves. We can examine our ideas, try them out, and discuss them. As designers, we’re familiar with this idea of getting something down on paper and building on it over time. You might call it iterating or agile, but I see that approach as the design process and I approach writing in the same way.

Writing is design

Our work is interrelated. We build these intricate, growing, and imperfect systems — threading complicated flows of information together with strings, colors, and boxes. We’re quilting this web, deliberately or not. And we have similar skills:

- critical thinking

- communicating

- planning

- organizing

- dealing with ambiguity

We think about systems and care about details. And we can see a better outcome or product than what’s there today. We also have similar goals when we’re writing or designing. We’re here to inform; to solve or reduce problems; to create lasting work; and to make the world a better place.

We have a similar process too. We:

- ask questions

- balance constraints

- learn about our clients and their audiences

- shape systems

- gather feedback

- build on what we know

Ultimately, we all listen, plan, compose, and revise. And our materials are intertwined.

Copy is interface

The words on your website shape how people think about your products, how they use them, and how they talk about them. Every piece of copy is part of your design.

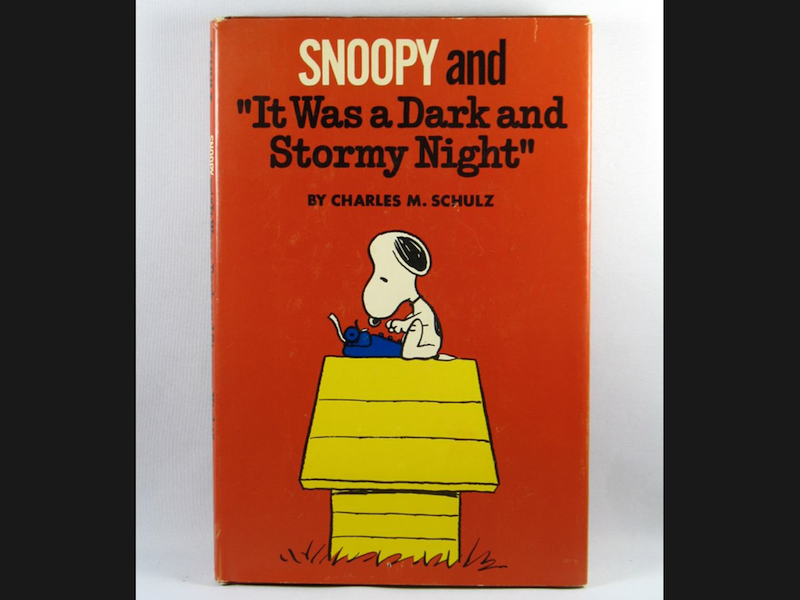

But the fact is a lot of designers still rely on lorem ipsum. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve come into a project, hired to do light copyediting, and the design was completely broken, because it was just a reskin or a layer of paint. If we can’t be bothered to understand the problems our clients are experiencing below the surface, we’re never going to solve anything with design.

Just to be clear, when I say writing, these are the things I’m talking about:

- alerts

- blog posts

- emails

- errors

- forms

- instructions

- labels

- names

- policies

- promotions / ads / marketing

- strings

- tours

Individually, these are all bits of text. Together, they’re your communications and your interface with readers. They make up your voice and tone. They give your product personality.

To communicate

Writing and design are both about communicating. The internet is a mass communications platform. And language is our most fundamental technology. Kevin Kelly says just that in his book, What Technology Wants.

This is a pretty beefy quote, so we’ll chew through it together. He says:

“Language accelerates learning and creation by permitting communication and coordination.”

With words, we can share ideas, talk to each other, learn from each other’s mistakes, and make new things.

“A new idea can be spread quickly if someone can explain it and communicate it to others before they have to discover it themselves.”

Language is a shortcut. It’s also a time warp and a sort of immortality. And then he says:

“But the chief advantage of language is not communication but autogeneration. Language is a trick that allows the mind to question itself; a magic mirror that reveals to the mind what the mind thinks; a handle that turns a mind into a tool. With a grip on the slippery, aimless activity of self-awareness and self-reference, language can harness a mind into a fountain of new ideas.”

Language is how we get unstuck. I think this is incredibly exciting and important and relevant to what we do. Long before the internet and the printing press, language gave us a way forward.

Fun fact, also from the book: technology is made from the words techne and logos. Techne is a Greek word, which means (1) skill of words, (2) speech about art, and (3) craft or craftsmanship. It’s also been translated as ingenuity. So if we think about language as our most basic technology, I think it’s our responsibility to be clear. This is our craft: building understanding, starting in ourselves.

Kevin Kelly says:

“[E]very technology—no matter its origin—can be channeled toward more transparency, greater collaboration, increased flexibility, and greater openness.”

If we’re willing to accept those four principles, I think having a beginner’s mind is the first step to going about them.

Writing helps us overcome our limits and overcome the past. It gives us a foundation for building the future, and a common language. It lets us discuss ideas, move them around, and share them across borders. We can outlive our deaths, speak to people in languages we haven’t learned, and change the course of history.

Where to begin?

I want to switch now to being a little more practical and share how I’ve become a better writer. Writing, like reading, is a very personal act. That’s why I think of it as a practice. But maybe some of the things I do will be useful to you too.

Think like a designer

I know there are some writers in the audience, people who don’t necessarily think of themselves as designers. And I know there are some designers who want to learn more about writing, but aren’t sure where to start. One of the first things that I would say to you is to talk to each other. If you’re a writer, sit with your designer. And when you’re writing, try to think like a designer, at least part of the time.

The most important thing to remember when you’re working on interface content is that you’re working with a system. That system needs to support the needs of its readers or users, whether you’re building for internal use or making something for the public. We have to work through the implications of each little decision we make, seeing them add up and braid into a whole.

When we can look at our writing or communications as a system, we can begin to understand why we need to be flexible — and why we need to think about writing a little differently than we did in the past. As designers, we try to make the best thing we can with the time and materials we have. We accept constraints, but also know we change things over time.

Our writing should have that same flexibility and fluidity. We shouldn’t talk about things as if they’re final, as if they live in their own individual universes. And when we put something into the world, we shouldn’t use words like postmortem that make us feel like we’re no longer responsible for those things. Everything we build depends on us. We have to nurture our work and know it’s going to continually change. And if you’re working with a client as a freelancer, it’s really your responsibility to teach your client how to keep nurturing their site without you.

Now, I’m a surfer and I love the ocean, so I use this metaphor of water and fluidity a lot. But I think we need to take this approach when we think about writing. We can embrace the chatty, shifting nature of the web. We can start small and build from there. Maybe we have a paragraph and build it out into a page later. Or maybe we launch without a blog until we can support that. Our work isn’t fixed. Everything can evolve.

Go places you’ve never been

When I was 14, I knew I wanted to be a writer. I lived in a suburban town in Texas. There wasn’t much to do there, so I wrote a lot of poems and decided I wanted to study photography. I took a course in the evenings at a junior college and managed to get a really good teacher. He showed me work from Cartier-Bresson, Nan Goldin, and Robert Mapplethorpe at a young age. But I liked Diane Arbus’s work the best. She photographed kids in the park, circus freaks, artists, and nudists. People on the fringes. And in her book, she says something I still think about:

“My favorite thing is to go where I’ve never been…If I were just curious, it would be very hard to say to someone, ‘I want to come to your house and have you talk to me and tell me the story of your life.’ I mean people are going to say, ‘You’re crazy.’ Plus they’re going to keep mighty guarded. But the camera is a kind of license.”

Photo walks are always an excuse to go somewhere new. I think they’re a nice physical way to practice beginner’s mind. Even throughout my 20s, I would creep into old, abandoned buildings or take photos of strangers. It’s not always safe, sure, but I got to see things I wouldn’t see otherwise.

I think writing is a license too. An excuse to be a little nosy or wedge into a conversation. You can try on different styles. You can ask people questions without creeping them out. You can work on eliminating those dark corners for yourself and your readers.

So that’s the first way I get better at writing. I go places I’ve never been. I ask questions and learn about things that may seem unrelated to what I’m looking at. I try to use my curiosity for good.

To work with this premise, I had to realize that everything is connected. All of those strings and colors and boxes are quilted together, and if I refuse to take the time to learn about them, I’m never going to solve any problems at all.

If you’re not sure where to start, try a flow in your product or a section on your website that you’re unfamiliar with. Get to know it. Write down questions you have. Write down things you notice, just as you would if you were holding a camera or writing about an adventure. Talk to people. Ask them what would make their lives easier.

You may be wondering if I’m advocating for a waterfall process or a huge amount of research before you start writing. I’m not. And that leads me to the second thing that’s helped me be a better writer.

Start in the middle

I used to try to write the beginning of something before I knew where we were going as a team. I would try to introduce the ideas I needed to cover and organize them, even though I didn’t fully understand those ideas yet. And that doesn’t give me a lot of room to change my mind, which I do pretty often.

So now I start in the middle. I get the most basic thing I know down on the page or the whiteboard, and work my way out, showing my client or my friends, whoever that set of beta readers is for the project, and making it better as I go.

Writing can be a research tool and help you workshop an idea. This is how I cook too — by fumbling along in the right direction. There’s a beautiful book by Tamar Adler called An Everlasting Meal. She says:

“Instinct, whether on the ground or in the kitchen, is not a destination but a path. The word instinct comes from a combination of in meaning ‘toward,’ and stinguere meaning ‘to prick.’ It doesn’t mean knowing anything, but pricking your way toward the answer.”

This is how I write. I start with what I have, and then prick my way toward the answer. Make it up and go from there. Throw words around on the page. These exercises can take many forms. I like to do a sort of Mad Libs or write a bunch of copy directions. The goal is to start writing, get the conversation going, and get your client involved in their communications.

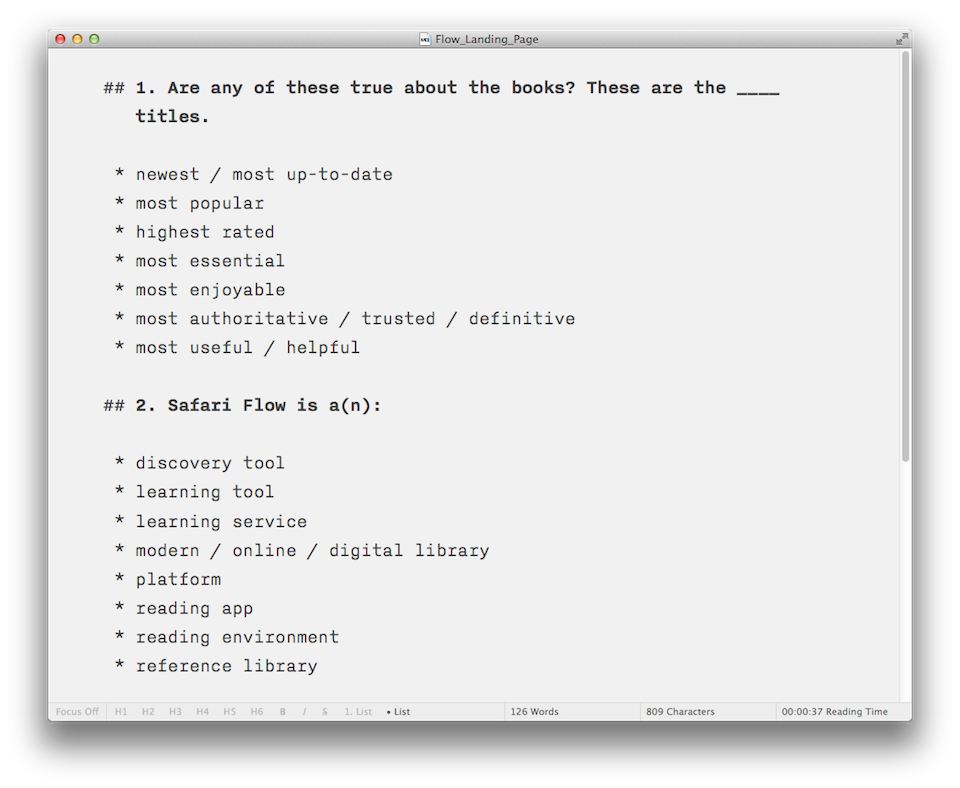

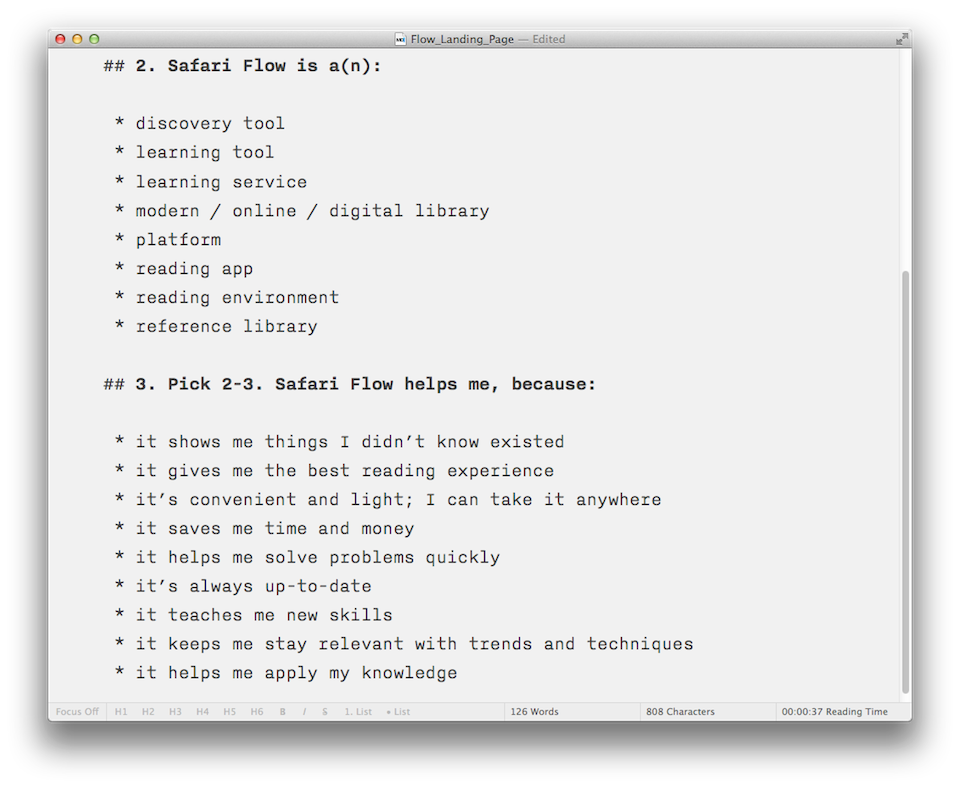

Here is a sample exercise from something I did recently with a client.

I do these sorts of things over and over again. I try to understand the words my client uses and develop a shared language around the product, so we can talk about it — and then figure out how to talk about it to the public. This is really useful for coming up with the name of something, a tagline, a mission statement, a feature intro, or any kind of writing that the rest of the product depends on. The pieces that have to be crisp and clear come from a very messy place.

Once I know what we’re talking about and the team has a shared vocabulary, it’s much easier to work on changes. And we know it’s not a product, it’s a publication, or who it’s for, or why it’s going to be in existence. From here, it’s 10 times easier to build understanding with readers, because I’ve already built that understanding within myself, within the team, and within the copy that we may or may not publish.

- Design the words so they can change as your mind does.

- Use little, simple layered chunks that are easy to move around. Sentences will do. If you build on those, teeny paragraphs with headers.

Now if you look at this, it may seem familiar. I think this is a very similar process to making design concepts, but instead of using colors and type and images, I’m using words and sentences and structure. Sometimes, I show other websites as examples too.

Writing is ultimately about helping people understand things, shaping the feeling, and showing people the way. While our materials may be different, we’re doing the same thing.

Write the way you do

The last thing I want to share is that I learned to write the way I do. This phrase comes from Several Short Sentences About Writing by Verlyn Klinkenborg. I found this book earlier this year, and it’s full of good advice. He says:

“Part of the struggle in learning to write is learning to ignore what isn’t useful to you and pay attention to what is…This is a book full of starting points. Perhaps they’ll help you find enough clarity in your own mind and your own writing to discover what it means to write. I don’t mean ‘write the way I do’ or ‘write the way they do.’ I mean ‘write the way you do.’”

This is another place where beginner’s mind can be useful. There’s a lot of advice about writing out there — including everything we learned in school, and the styles we’ve read in books and articles over the years. I come to writing like I come to cooking or yoga. It’s a practice where I can pick out the techniques or styles that work for me and ignore the rest. I’m always changing things up too.

Here are three things that work for me. But please know I don’t mean these as advice so much as to share what I do. I’d love to hear what works for you too.

It doesn’t matter what time of day it is. But I have to write almost every single day. Sometimes I write in the morning and sometimes at night. Sometimes I write onto paper or onto the screen. Sometimes I talk into my phone, transcribing my thoughts or recording them for later. I don’t really care about the tools, though I do love Editorially and I also find iA Writer to be useful. It’s not about where I am or when I am or even how I am.

The first thing I have to remember when I’m writing is that it’s hard and I can do it. Honestly, it’s just a bunch of sentences, one idea after another. Keeping that beginner’s mind helps me. I read more. I write more. I don’t worry about where I’m getting to. I find new ways to say things or new connections, new stepping stones. And I feel more confident, because I’m always curious.

Writing can be scary, but it can also be rewarding. I have to remind myself that that voice, that nagging voice that makes me nervous or tells me that I have nothing important to say, is worth listening to for about 25 seconds and then shoving into a jar or out the window. I have to keep asking questions and stumbling along, remembering it’s normal.

I also have to remember to stay in my chair. Committing the time to actually sit with the words and look at them is where the work is. As Klinkenborg says, writing is about the endless winnowing of sentences. Sentences are the work. You might call it patience, focus, or determination. But for me, it’s often about the practice itself and the time it takes to look at my screen — and not look at Twitter or be distracted by chocolate or my husband or my dog or New York City or whatever it is.

I also have to remember to use my voice. It took me years to stop copying other people’s styles and to stop writing how they teach you in school, where you’re making arguments instead of sharing what you notice.

Use your voice and write about what you notice. That’s your material. You can show people things they’ve never seen before. Take them to places they’ve never been.

The way I learned to use my voice is to read things aloud. I try to write to someone as if they’re sitting at my kitchen table. I’ve invited them in; they’re someone I know and care about; they’re sitting at my table, listening to my story; I want to give them a reason to stick around. Or maybe they’re a friend I haven’t seen in a while who lives on the other side of the world. I see them there, reading my letter, and that helps me remember to sound like me instead of a robot, a lawyer, or a journalist reporting the facts.

Your sentences can be simple and short. That’s what I love about Verlyn’s book. He points out the nonsense that we have to make arguments, have a thesis, or use long sentences to explain things. The more concise we are, the easier it is to follow along.

So that’s I wanted to talk about today. I hope you find a way to begin. You don’t need to know anything. You only need to ask. Read books and edited text. Write your heart out. Find your beta readers. Be kind to each other. There is no secret.

Thank you.

Further Reading

- Nicely Said: Writing for the Web with Style and Purpose

- Not Knowing, a collection from Austin Kleon

- Writing Prompts from Luke Neff

- The Art of Communicating by Thich Nhat Hanh

- Writing to Change the World by Mary Pipher